Hace unos días os anunciábamos la publicación en España del libro “Años Salvajes”, escrito por el periodista y surfista William Finnegan, y galardonado con el Premio Pulitzer 2016. En Surgere tuvimos el placer de leer el libro unas semanas antes de su publicación y compartir con vosotros nuestras impresiones.

No tenemos duda de que el libro os va a enganchar tanto como a nosotros, y por eso os hemos preparado una sorpresa. Recientemente hemos podido charlar con William y no sólo eso, sino que tenemos un ejemplar de “Años Salvajes” firmado por él y dedicado en exclusiva para los amigos de Surgere Magazine. ¡Estad atentos porque pronto os diremos cómo podéis haceros con él! Ahora, os dejamos con la charla que hemos tenido con él.

Solamente al verle acercarse, ya se aprecia que estamos ante una persona con una capacidad cautivadora innata. De mirada serena y sonrisa amplia, William no puede negar su procedencia Norteamericana. A sus 63 años y debajo del traje, uno se lo imagina fácilmente enfundado en un neopreno y con una tabla bajo el brazo.

Como periodista has cubierto conflictos armados, políticos, catástrofes,… por todo el mundo. ¿Cómo logra uno mantener la cabeza en su sitio tras haber vivido esas cosas? ¿es posible regresar a casa tras cubrir una guerra siendo la misma persona?

Para un periodista del primer mundo, cubrir guerras civiles, la desesperación política y económica, y las emergencias humanitarias en los países en desarrollo requiere de un cuidadoso equilibrio de desapego y empatía. Es diferente para cada reportero, pero conseguir ese equilibrio bien puede marcar la diferencia entre un buen trabajo y un trabajo mediocre y es fundamental para mantener tu salud psíquica y emocional. Tienes que ver a la gente sobre la cual estás escribiendo como personas, y tratar de entender cómo sienten y ven ellos las cosas. Al mismo tiempo, hay que tratar de evitar sentirse tan angustiado por su situación y por su sufrimiento, que tu historia se salga de foco, por la responsabilidad que tienes hacia tus lectores de producir una narración precisa. Normalmente hago viajes para hacer reportajes, luego regreso a casa para escribir, -así que no soy reportero de noticias; normalmente no necesito escribir historias en el terreno y con la urgencia de la inmediatez. Tampoco soy un corresponsal extranjero, en el sentido de que vivo en Nueva York. Pero volver a casa puede resultar muy desorientador. Por ejemplo, acabo de terminar una historia sobre la crisis en Venezuela. No es un conflicto armado, pero hay una situación grave de hambre generalizada, una escasez crítica de medicamentos y suministros médicos, y un nivel aterrador de crímenes violentos. Después de volver a casa, me costaba caminar en mi propio bloque por la noche, estaba en un estado de alerta extrema, siempre mirando entre las sombras y mirando detrás de mí. Insistía a familiares y amigos para que fueran más cuidadosos en público, cuando en realidad no había absolutamente nada de qué preocuparse. Me parecía increíble, injusto, que los supermercados estuvieran tan llenos de comida y siempre había buenos hospitales y médicos especialistas disponibles si era necesario. Por supuesto, ese tipo de desorientación se pasa en pocas semanas, pero viajar regularmente entre mundos definidos por problemas, violencia y pobreza, por un lado, y el pacífico y próspero Occidente, por el otro, produce a largo plazo -por lo menos en mi caso-, una profunda apreciación de, en primer lugar, las comodidades que tendemos a dar por sentadas y, en segundo lugar, la fragilidad última de las instituciones políticas democráticas y los lazos sociales. En Occidente somos muy afortunados, pero la continuidad de nuestra “buena suerte” no está garantizada.

¿Te ayudaba en esos momentos pensar en el surf, a modo de evasión?

Sí, es una extraña comodidad y una distracción agradable pensar en el surf cuando el mundo parece un lugar oscuro y horrible.

¿En algún momento debes enfrentarte al conflicto interior de elegir entre el surf y el periodismo?

Nunca dejé de surfear. A veces pasaba unos meses sin poder hacerlo, mientras vivía en lugares alejados del océano, pero nunca más de un año entero. Y nunca hubo un conflicto directo entre el surf y mi carrera periodística para mí. Mudarme a Nueva York desde San Francisco fue, sin embargo, una elección definitiva de mi carrera por encima del surf, y durante un tiempo estaba preocupado porque creía que no sería capaz de surfear tanto como yo quería. Pero pude hacer muchos viajes para surfear y luego descubrí que hay buenas olas cerca de Nueva York, especialmente en otoño e invierno. Así que empecé a surfear allí, y ahora lo hago todo el año en Nueva Jersey y en Long Island. También viajo todo lo que puedo a Hawaii, México, Indonesia, y otros lugares con grandes olas.

Como surfista te has enfrentado a la muerte en más de una ocasión. Como corresponsal de guerra también. ¿Crees que son situaciones equiparables?

Puede haber una ansiedad similar, sobre todo antes -la noche anterior-, cuando se sabe que las olas van a ser grandes, o que el trabajo del día siguiente puede ser peligroso, y es difícil dormir, o incluso relajarse. Pero las situaciones son completamente diferentes. Al surfear olas grandes (y matizo “grandes”, porque no surfeo “las más grandes”, -eso es sólo para especialistas), puedes confiar en toda una vida de experiencia oceánica y tus habilidades (surfing, remada, natación, capacidad de aguantar la respiración) para mantenerte relativamente a salvo, para tomar solamente riesgos cuidadosamente calculados. Cuando informas sobre conflictos, tienes mucho menos control. Las personas actúan impredeciblemente, las situaciones de repente se intensifican, los bombardeos y los disparos y la violencia pueden ser bastante aleatorios, -el factor suerte es mucho mayor. Dicho esto, siempre se pueden tener precauciones, o tomar decisiones que reduzcan el riesgo de ser herido o capturado. Además, hay que tener en cuenta que los redactores de prensa escrita como yo no se ven obligados a asumir riesgos al mismo nivel que los fotógrafos. Nosotros nos podemos esconder debajo de la cama en nuestra habitación de hotel y aun así posiblemente encontraríamos alguna historia que contar. Los fotógrafos y cámaras deben seguir el infame dictum, “Acércate más.” En realidad dejé de hacer reportes de guerra al nacer mi hija, en 2001. Todavía escribo sobre la violencia política, y todavía trabajo en algunos lugares con mala seguridad -he escrito un serie de artículos en los últimos años sobre la delincuencia organizada en México, por ejemplo, a veces reportados desde áreas controladas por cárteles. Pero eso es muy diferente del reportaje en el campo de batalla. Me interesa la política, el poder, la justicia y los derechos humanos, no la estrategia militar.

En el libro descubrimos dos búsquedas, la de la ola perfecta, y la del sentido de la existencia. Tras pasar gran parte de tu vida en busca de ambas, ¿crees que verdaderamente existen, o se trata de algo subjetivo, algo diferente para cada uno de nosotros, algo que siempre estamos persiguiendo, pero quizá está dentro de nosotros?

La segunda parte de la pregunta es la clave. Eso es precisamente lo que pienso, respecto a lo que llaman el “significado de la existencia”. En cuanto a la ola perfecta, es una idea, no una realidad. Hay grandes olas, magníficas olas, que viajamos por el mundo para encontrar y surfear, pero no son objetos fijos de contemplación en la naturaleza, como un diamante o una rosa. Son rápidas, eventos violentos, colisiones de la energía del océano y la tierra, y cada una es diferente. La perfección es una palabra que usan los surfistas, pero es un concepto muy torpe, mal ajustado cuando se aplica a algo tan salvaje, evanescente y único como una ola. También, por supuesto, la ola “perfecta” de un surfista puede ser la pesadilla de otro, demasiado difícil y peligrosa para él, quizás, o simplemente no apta para su estilo o habilidades.

¿Qué significa para ti, tras 5 libros, amén de toda una trayectoria periodística, recibir el Pulitzer con “Años Salvajes”?

Es irónico, supongo, porque los Pulitzers están fuertemente asociados con el periodismo, y éste es mi libro menos periodístico. Pero también premian a novelas y obras de teatro, así que ¿por qué no una para unas memorias? Me siento profundamente honrado. Ojalá mis padres estuvieran vivos. Estarían aún más emocionados que yo.

Se ha calificado “Años Salvajes” como el mejor libro de surf de la historia. ¿Estás de acuerdo?

No es un libro de historia de surf. Es historia personal, con mi obsesión por el surf como hilo narrativo. El mejor libro de la historia del surf es “The History of Surfing”, de Matt Warshaw. También recomiendo, para los apasionados, la “Encyclopedia of Surfing” de Warshaw. Es un libro y una enciclopedia on line, contiene vídeos y estña en constante actualización.

¿Le recomendarías el libro a alguien que no esté relacionado con el surf?

Mi libro está escrito para el lector general, no para los surfistas. No incluyo un glosario, pero cada término técnico de surf es explicado, para lectores no surfistas, en el momento en que se introduce el término. Muchos lectores me han dicho, “Esto no es un libro sobre el surf,” cosa que me gusta mucho escuchar. Dicen: “Es un libro sobre los Hombres” o “Es sobre la amistad”, o “Es sobre el amor”, o “Es acerca de cómo vivir”. Son unas memorias sobre la juventud y la edad, el amor y el desamor, la amistad masculina, la literatura y la política, una obsesión particular y sus glorias y consecuencias, la vida y los tiempos de mi generación y algunos de los lugares locos donde he vivido y trabajado.

¿Qué valores crees que inculca el surf? ¿Hasta qué punto han sido valiosos/importantes para ti?

1) Auto-confianza: nadie puede ayudarte en el agua. Estás por tu cuenta y dependes de ti mismo. 2) Humildad: estás obligado a respetar el poder y la belleza del océano. 3) Irresponsabilidad y egoísmo: no hay nada más socialmente inútil e improductivo que el surf, y sin embargo, una vez que estás enganchado, pasarás muchos años y emplearás cantidades increíbles de energía persiguiendo olas, meramente para tu propia satisfacción.

En “Años Salvajes” hablas del significado del surf en Hawaii, donde es algo cultural, e implica un respeto hacia y entre los surfistas. ¿Has encontrado lo mismo en otras partes del mundo?

No. No en la misma medida que en Hawaii. En algunos lugares, se considera una actividad antisocial. La policía o las autoridades locales pueden ser hostiles hacia los surfistas. En otros lugares, es un “deporte” o pasatiempo aceptado y aprobado. En Australia, los campeones de surf son celebridades, como otros atletas de alto nivel. En los Estados Unidos, la mayoría de la gente no sabe nada al respecto. Ni siquiera pueden nombrar al 11 veces campeón del mundo, su compatriota Kelly Slater. Hawaii es especial porque es la cuna del surf, y está fuertemente asociado con la cultura indígena, incluso con la resistencia indígena a los valores de negocios calvinistas traídos por primera vez a las islas por los misioneros estadounidenses en 1820. Esos misioneros explícitamente trataron de eliminar el surf en Hawaii, y casi lo lograron. Las enfermedades traídas por los colonos y conquistadores a las islas casi exterminaron a los hawaianos. En poco más de un siglo, redujeron la población nativa en un 95 por ciento. Pero ellos continuaron surfeando, y hoy es una fuente de gran pasión y orgullo en Hawaii. Allí disfrutan de algunas de las mejores (y más grandes) olas del mundo.

Y ahora una serie de preguntas breves a modo de resumen:

Si pudieras retroceder en el tiempo, ¿dejarías de hacer algo de cuanto has explicado haber hecho en el agua y que ahora consideres innecesario y/o temerario?

Me arrepiento de algunas cosas, por supuesto, pero la respuesta es, sin duda, NO.

¿Mejor surfista con el que has tenido el placer de surfear?

Shane Dorian, en Fiji.

¿Con qué ola de todas las que nos explicas en el libro te quedarías?

Lagundri Bay, Pulau Nias, Indonesia. O Honolua Bay, Maui, Hawaii. O Rincon, California. O Jeffreys Bay, South Africa. El problema es que todos esos spots son muy conocidos y están masificados. Mi fantasía sería poder surfearlos en solitario, o sólo con unos pocos surfistas más. Pero es algo que nunca pasará.

¿Qué momento dentro del agua recuerdas con especial sentimiento?

Tavarua Island, Fiji, 1978. Una de las mejores olas del mundo, rompiendo una isla deshabitada, y por aquel entonces, desconocida en el mundo del surf. Dos de nosotros acampamos en la isla, alimentándonos con lo que nos daban los pescadores locales, y surfeando la ola en todas las condiciones.

¿Si tuvieras que escoger una playa, cuál sería?

No tengo playas favoritas. En realidad, apenas me fijo en las playas. Normalmente sólo me apresuro a cruzarlas, en busca de las olas.

¿Un lugar para vivir?

Estoy muy feliz en Nueva York. No es Hawaii, pero tiene olas, y mucha gente interesante, y siempre están pasando cosas. Creo que es un buen lugar para criar a nuestra hija.

Muchísimas gracias por tu tiempo.

Recordad que en nuestra tienda online también podéis haceros con un ejemplar de “Años Salvajes”

Os dejamos el vídeo resumen de la obra.

Años salvajes — William Finnegan (Booktrailer) from Libros del Asteroide on Vimeo.

Helga Molinero / Twitter: @HelgaMolinero

http://surgeremagazine.com/anos-salvajes-entrevista-a-william-finnegan/

Myles

laying down a powerful drop knee at Noosa. I was sitting in one spot to

get this photo and was shooting on film, which makes it even more

special to have the moment, light, and focus all line up perfectly. All

photos by Henry CousinsFor the past year, 19 year old photographer

Myles

laying down a powerful drop knee at Noosa. I was sitting in one spot to

get this photo and was shooting on film, which makes it even more

special to have the moment, light, and focus all line up perfectly. All

photos by Henry CousinsFor the past year, 19 year old photographer

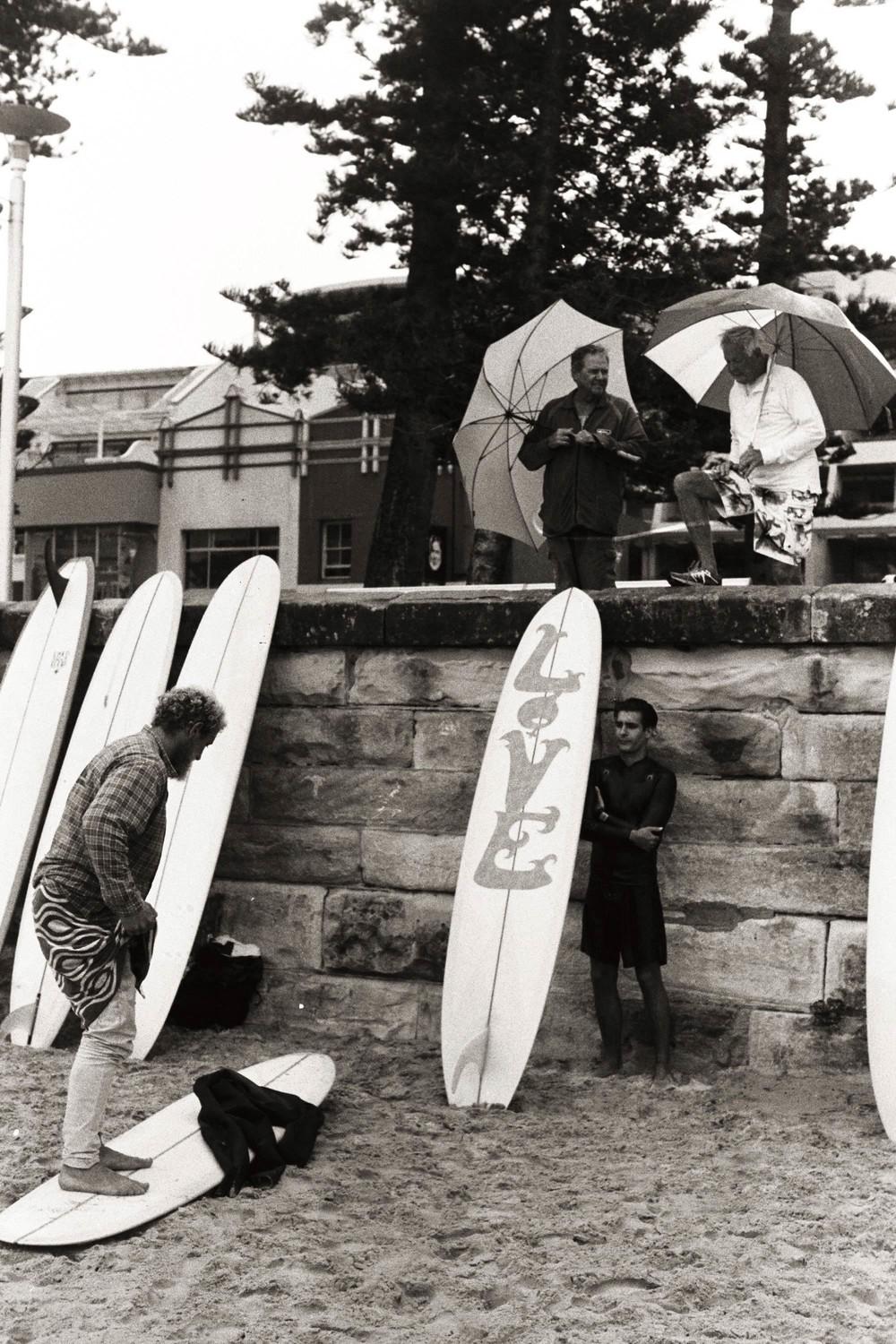

With each approaching set, the crowd cheered as perennial favorites

like Alex Knost and Justin Quintal, as well as newcomers like Andy

Nieblas, Riley Stone, Kelia Moniz and Karina Rozunko, ran through their

gears, perching noserides while arching gracefully back, trailing arm

extended above their head, the other calmly at their waist; hanging

heels before retreating swiftly toward the tail; bending their

single-fins through dramatic, sweeping cutbacks. This didn’t feel like a

sideshow, and, given the conditions, for many viewers on the beach and

at home live-streaming from their computers, this was the main event.

With each approaching set, the crowd cheered as perennial favorites

like Alex Knost and Justin Quintal, as well as newcomers like Andy

Nieblas, Riley Stone, Kelia Moniz and Karina Rozunko, ran through their

gears, perching noserides while arching gracefully back, trailing arm

extended above their head, the other calmly at their waist; hanging

heels before retreating swiftly toward the tail; bending their

single-fins through dramatic, sweeping cutbacks. This didn’t feel like a

sideshow, and, given the conditions, for many viewers on the beach and

at home live-streaming from their computers, this was the main event.

“Women’s longboarding is the absolute next big thing, no question,”

Tudor says. “Girls hanging ten, riding longboards beautifully—it’s

incredible. Especially because this generation of girls is so cool. Holy

shit, they’re inspiring. They each have their own style. You see them

all over the world, traveling to waves that fit their style. And it’s

amazing to see the younger girls looking up to them, and how they’re on

their own trip.”

“Women’s longboarding is the absolute next big thing, no question,”

Tudor says. “Girls hanging ten, riding longboards beautifully—it’s

incredible. Especially because this generation of girls is so cool. Holy

shit, they’re inspiring. They each have their own style. You see them

all over the world, traveling to waves that fit their style. And it’s

amazing to see the younger girls looking up to them, and how they’re on

their own trip.”

“It would be cool to see more kids able to earn a paycheck from

longboarding,” Tudor says. “But it’s working out. I can’t tell you how

many people have benefitted, who are surfing amazing, and on their own

trip, and when the waves get big or good they ride other stuff. Tyler

[Warren] and [Ryan] Burch, they’re the All-Board Generation. This crew

has figured it out.”

“It would be cool to see more kids able to earn a paycheck from

longboarding,” Tudor says. “But it’s working out. I can’t tell you how

many people have benefitted, who are surfing amazing, and on their own

trip, and when the waves get big or good they ride other stuff. Tyler

[Warren] and [Ryan] Burch, they’re the All-Board Generation. This crew

has figured it out.”